Pracownia Systematyki i Zoogeografii

Działalność naukowa systematyków, obejmuje:

- rozpoznawanie, opisywanie i nadawanie nazw taksonom (gatunkom, rodzajom, itd.) oraz rewizje dawniejszych deskrypcji, synonimizowanie nazw, etc.

- badania nad relacjami pokrewieństwa pomiędzy taksonami (filogeneza) oraz proponowanie dla badanych grup hierarchicznej klasyfikacji, jak najlepiej oddającej stosunki pokrewieństwa;

- przedstawianie hipotez dotyczących procesów ewolucyjnych, adaptacyjnych i innych, które mogły wpłynąć na powstanie obecnej struktury i rozsiedlenie badanej grupy;

- odkrywanie nowych zestawów cech służących identyfikacji (np. cechy odkrywane z pomocą nowoczesnych technologii, takich jak SEM);

- tworzenie narzędzi do identyfikacji taksonów (kluczy, monografii, rewizji) i ich używanie: identyfikacja; tworzenie list inwentarzowych specyficznych obszarów lub ekosystemów.

Powstające opracowania systematyczne, monografie, rewizje, wykazy i katalogi są niezbędne dla dalszych badań systematycznych, filogenetycznych, ewolucyjnych i zoogeograficznych; mogą być też wykorzystywane w biologicznych naukach stosowanych: w rolnictwie, sadownictwie, kwarantannie, medycynie, ochronie gatunkowej i siedliskowej, w badaniach bioróżnorodności i określaniu przyrodniczych obszarów szczególnie cennych.

Zakres działalności Pracowni i wykonywane zadania

- Działalność naukowo-badawcza - realizacja projektów badawczych:

- w ramach projektu statutowego MIZ - Filogeneza, klasyfikacja i biogeografia zwierząt; oraz w ramach projektów pozastatutowych i międzynarodowych programów badawczych (projekty finansowane przez MNI oraz przez zagraniczne instytucje, fundacje itp.)

- Współpraca z Działem Zbiorów:

- Wzbogacanie zbiorów naukowych Muzeum - pozyskiwanie materiału w czasie wypraw naukowych, z wymiany pomiędzy badaczami lub instytucjami oraz z pracy rewizyjnej i opisowej, podczas której oznaczane są materiały naukowe i typy opisowe.

- Opieka merytoryczna nad zbiorami: oznaczanie, katalogowanie, porządkowanie kolekcji, włączanie nowych okazów do kolekcji oraz prace rewizyjne (w obszarze swoich grup zainteresowań).

- Współpraca z Działem Upowszechniania, Promocji i Rozwoju:

- Uczestnictwo i współpraca w programach ramowych Unii Europejskiej, np. SYNTHESYS i EDIT

Główne projekty badawcze (aktualnie realizowane)

- Trends in the latitudinal distribution of the freshwater copepod family Cyclopidae.

- Phylogenetic utility of combined molecules and morphology in the freshwater copepod Mesocyclops (Crustacea: Cyclopidae).

- Klasyfikacja południowo-wschodnioazjatyckich chrząszczy z podrodziny Megalodacninae (Coleoptera: Erotylidae).

- Taksonomia, systematyka i biogeografia australijskich biedronek z podrodziny Coccidulinae (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). (grant ABRS).

- Rewizja taksonomiczna chrząszczy z rodzaju Rhyzobius Stephens (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). (grant NSF).

- Rekonstrukcja historii ewolucyjnej ssaków drapieżnych.

- Taxonomic revisions complementing Monograph of the Salticidae (Aranae) of the World. (grant MNI).

- Aktualizowanie komputerowej bazy danych “Monograph of the Salticidae (Araneae) of the World” <http://www.miiz.waw.pl/salticid/main.htm>

Szczegółowe informacje o badaniach prowadzonych przez pracowników Pracowni można znaleźć na ich indywidualnych stronach.

Stacja Badawcza Fauny Karpat w Ustrzykach Dolnych

Cele działania i osiągnięcia

Prace prowadzone w Stacji Badawczej Fauny Karpat, Muzeum i Instytutu Zoologii PAN - zlokalizowanej w Ustrzykach Dolnych, koncentrują się na zagadnieniach związanych z funkcjonowaniem populacji dużych ssaków w naturalnych i przekształconych ekosystemach eko-regionu karpackiego.

Od 1999 roku koordynowany jest tutaj prowadzony we współpracy z RDLP Krosno program restytucji żubra w Karpatach, obejmujący monitoring istniejących stad (częściowo z użyciem telemetrii), analizę dynamiki i struktury ich areałów, genetyczną strukturę populacji oraz planowanie i organizacja wsiedleń żubrów w celu obniżenia inbredu w wolno żyjących stadach i powiększenia areału tej populacji. Program prowadzony jest we współpracy z partnerami z Rumunii, Słowacji i Ukrainy. Podsumowaniem ponad 10 lat tej współpracy jest monografia „Powrót żubra w Karpaty”, która ukazała się w roku 2012. W roku 3013 zakończono ocenę możliwości rozprzestrzeniania się żubrów z populacji bieszczadzkiej na zachód, t.j. na teren Beskidu Niskiego w kierunku Magurskiego Parku Narodowego, ze wskazaniem potencjalnych korytarzy migracyjnych. Kontynuowany jest projekt kolekcji włosów i tkanek żubrów dla oceny zmienności genetycznej tej populacji oraz dwukrotnie w roku prowadzony jest zbiór odchodów dla oceny stanu zapasożycenia.

W roku 2014 uruchomiony został projekt monitorowania przemieszczeń się żubrów z użyciem telemetrii GPS.

Zrozumienie procesów przyrodniczych zachodzących obecnie w Bieszczadach, jest niemożliwe bez znajomości wyjątkowo tu skomplikowanych i unikalnych na skalę europejską zmian, w systemie użytkowania gruntów i kierunków rozwoju ekonomicznego tego regionu. Jednym z tematów badawczych prowadzonych w Stacji są więc historyczne przekształcenia środowiska przyrodniczego Bieszczadów na przestrzeni ostatnich 150 lat. Analizowane są antropogeniczne zmiany środowiska przyrodniczego w Bieszczadach Zachodnich na podstawie źródeł historycznych. Na ten temat ukazały się już drukiem trzy opracowania monograficzne.

Stacja latem

|

Stacja jesienią

|

Stacja zimą

|

Informacje dodatkowe:

Spis wszystkich publikacji Stacji

Pracownia Owadów Społecznych i Myrmekofilnych

The Ants of Poland

About Polish myrmecology in brief

The tradition of Polish myrmecology goes back to the 18th century. Yet for the first half of the 19th century, a period when European myrmecology enjoyed a rapid development, there are only few general lists of ants from Poland, and they include species names that in many cases cannot be identified now. Only in the second half of the 19th century were some more detailed faunistic lists compiled.

The true development of Polish myrmecology began in the first half of the 20th century, after World War I; many faunistic lists covering large parts of the country were published then. Most studies were discontinued during World War II, but already in the first years after the war several faunistic and ecological myrmecological papers appeared. The period from the end of the 1950s through the 1960s was a time of a rapid development of Polish myrmecology. The output of this period included numerous papers on ant faunistics, taxonomy, ecology, ethology as well as on the role of ants in forest protection.

The scope of myrmecological studies in Poland expanded even further in the 1970s and 1980s; there were begun investigations into the social organization of ant colonies, into the composition, structure and development of multi-species assemblages in different natural and anthropogenic habitats, into bionomics and competition, and into socially parasitic relations.

At the turn of the 1980s and the 1990s, the Polish myrmecological literature dealt not only with the still prevailing questions about the role and occurrence of wood ants, but also with other issues, such as the theoretical and practical aspects of their artificial colonization. The threads of breeding behaviour of ants and their reproductive strategies, as well as new ethological questions also appeared then.

Recent taxonomic and faunistic investigations undertaken by the team of the Laboratory of Social Insects, MIZ PAS ? based both on freshly collected materials and on revised rich museum collections ? contributed to verification and to explosive enrichment of the knowledge of the ants of Poland. As a result, the Polish myrmecofauna has become one of the best known local myrmecofaunas in Europe.

The monograph

The recapitulation and the crowning achievement of - aged more than two centuries - the Polish myrmecological faunistics is a monograph "The Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Poland" by W. Czechowski, A. Radchenko and W. Czechowska. The monograph contains 98 species of 25 genera and four subfamilies whose occurrence in Poland has been either confirmed by the authors or at least considered probable. The book consists of three parts. The first part is a catalogue of the ants of Poland, and provides a taxonomic review of the species together with information about their geographical ranges, occurrence in Poland and biology. It has been prepared by compiling all literature data up to the year 2000 on the occurrence of particular species in Poland, with regard to the division of the country into geographical regions. The second part is a characteristics of the Polish myrmecofauna, including its zoogeographical and ecological composition. The third part consists of keys for identification of the ants of Poland based on recent taxonomy.

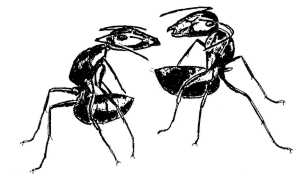

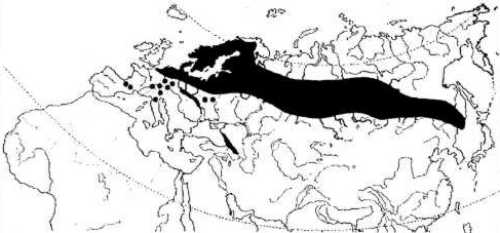

Species distribution in Palaearctic and in geographical regions in Poland, exemplifying by Harpagoxenus sublaevis - a socially parasitic ant species.

About Polish ants in a few words

The 98 ant species in Poland, including 93 outdoor species, form a big number in comparison with the ca 300 species occurring throughout Europe. In two neighbouring countries, in Germany and in Ukraine, both well?studied in the myrmecological respect, bigger than Poland and physiographically more varied, the number of known ant species is 110 and about 140 respectively. Merely about 60 species have been recorded from Belarus, and about 100 from the Czech Republic and Slovakia together.

The core of the Polish myrmecofauna is made by common species occurring all over the country or in most of it. At present, there are 11 species (12% of the outdoor myrmecofauna; Myrmica rubra, M. ruginodis, M. rugulosa, M. sabuleti, Tetramorium caespitum, Formica rufa, F. polyctena, F. truncorum, F. sanguinea, Lasius niger, L. flavus) recorded from all geographical regions.

On the other hand, in the Polish myrmecofauna there is a great proportion of rare species. As many as 14 species (15% of the outdoor myrmecofauna) are known from one site only (e.g. Myrmica hirsuta, L. nadigi, Doronomyrmex kutteri, Epimyrma ravouxi, Formica uralensis, Camponotus piceus, Lasius nitidigaster) and 18 other species (19%) from 2?5 sites mostly situated in different regions of the country (e.g. Tapinoma ambiguum, Myrmica hellenica, Leptothorax clypeatus, Formica lugubris, Lasius bicornis).

Dry stems of Cynanchum vincetoxicum and other herbs in the Pieniny Mts (S Poland) are the typical nesting place of Epimyrma ravouxi, a very rare social parasite, and some of its equally rare slave species of the genus Leptothorax.

Publication: Czechowski, W., A. Radchenko and W. Czechowska. 2001. The Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Poland. Museum and Institute of Zoology, Warszawa (in press).

***

Competitive Relations and Social Parasitism in Ants

General rules of competition in ants

Ant multi-species communities have a hierarchic structure. The hierarchy consists of three main levels. The lowest level is represented by species which defend only their nests. The intermediate level consists of species which defend their nests and food sources. The highest level is occupied by species which defend the nest and the whole foraging areas, i.e. territorial species.

A nest of Formica polyctena, a wood ant species, an typical representative of territorial ants.

Nests of territorial ants form centres of spatial organization of local communities. Subordinate ant species may live in a dominant's territories, but their abundance there is smaller, foraging activity reduced, reproductive potential lower, and they may nest only at a certain distance from the dominant's colony, determined by factors affecting its social organization. The relations between wood ants, e.g. Formica rufa and F. polyctena, (dominant species) and F. fusca (subordinate species) perfectly reveal the essence of the matter.

Under certain conditions, however, the proximity of a stronger partner appears to be advantageous to subordinate species. This happens when subordinate species stand face to face with danger from social parasites.

The scene of action

A complex of sand dunes gradually overgrowing with pine forest, southern Finland.

Sand dune habitat, S Finland.

Characters in the play

Lasius fuliginosus and Formica rufa - aggressive territorial species, thus representing the highest level of hierarchy; dominants of local ant communities.

A nest of a territorial ant species, Lasius fuliginosus.

Formica sanguinea - a socially parasitic species that practises facultative slavery; very aggressive ants that during their raiding period do not respect the boundaries of other species' territories.

Workers of Formica sanguinea, a facultative slave maker.

Formica fusca and F. cinerea - slave species of F. sanguinea; the former is non-aggressive and non-territorial form, typical representative of the lowest level of hierarchy; the latter is aggressive and territorial species.

Nest complex of Formica cinerea - a very common slave species of F. sanguinea in sandy habitats.

Episode one

F. sanguinea attacked F. fusca and F. cinerea colonies in the vicinity of a L. fuliginosus territory. F. fusca and F. cinerea workers from raided nests, fleeing side by side from F. sanguinea, headed towards the territory of L. fuliginosus. In replay to this, L. fuliginosus ants formed a dense cordon along a threatened section of the boundary. The strangers' attitude towards L. fuliginosus (and vice versa) varied depending on the species and its hierarchical status. F. fusca workers dispersed and singly picked their way among L. fuliginosus and thus managed, almost unobstructed, to get far inside the territory where - together with their rescued brood - they waited until the danger was over. On the other hand, F. cinerea workers, although panic-stricken, never crossed the boundary, even they met no L. fuliginosus cordon. It was only F. sanguinea workers that attacked L. fuliginosus ants and were attacked by them.

Episode two

Scouts of F. sanguinea are able to pass through a L. fuliginosus territory unnoticeably as dispersed penetration is very poor in the latter species and most its routes run in underground tunnels. Due to this, scouts had detected a F. cinerea nest opposite the territory of L. fuliginosus. But two succeeding attempts of a F. sanguinea raiding column to pass the territory failed after the raiders had come up against a cordon of L. fuliginosus posted on the boundary. In the end, the raid aiming at the choosen slave species nest was conducted along a route bypassing the L. fuliginosus territory, 20% longer and technically much more difficult than the possible rectilinear route. An about 20-m-long fragment of raid route ran along the very edge of the boundary. Throughout the two-day raid, this section of the boundary was densely lined with L. fuliginosus ants which prevented the F. sanguinea column from taking any short-cut.

Episode three

F. sanguinea raided a F. fusca nest within the territory of a small F. rufa colony. The attackers quickly took over the entire F. fusca nest area and were beginning to carry home captured pupae. At first, F. rufa ants reacted to this by forming a dense cordon close to their nest. Then, the cordon moved, reached the middle of the nest area of F. fusca, ousteding F. sanguinea from there. Both sides avoided confrontation and direct encounters between them were rare. At the same time, F. sanguinea robbed freely pupae from the part of the F. fusca nest that was not protected by F. rufa. Next, F. rufa forced out F. sanguinea from the entire area of F. fusca nest and thus it saved the slave species colony from total destruction.

Episode four

F. sanguinea started a raid towards a habitat settled by numerous colonies of F. fusca and a large colony of F. rufa. When the attackers reached their target, they began to plunder the slave species colonies. Moving from one F. fusca nest to another, they covered an area of about 50 m2 and approached the F. rufa territory. Wood ant workers formed an arched, 10 m long mobile cordon along their boundary. Although not dense, the cordon proved impassable for F. sanguinea, however, F. fusca ants fleeing with their pupae from the danger zone, passed through the cordon freely. Throughout the duration of the raid, F. rufa maintained its cordon which divided the F. fusca population into two parts: one left a prey to F. sanguinea and the other effectively protected by the colony of wood ants.

Question on the balace

In the light of the above a question arises of F. fusca's (as a subordinate and at the same time a slave species) balance of profits and losses connected with nesting in territories of territorial ants in areas situated within reach of F. sanguinea raids. On the one hand, a dominant species strongly competes with subordinate species and thus affects it restrictively. On the other hand, however, territorial ants - when protecting boundaries of their own foraging area - automatically protect slave species against their social parasites. As special investigations have shown, when a danger from F. sanguinea is lacking, abundance of F. fusca in a territory of wood ants is significantly lower than outside a territory. The picture is entirely different in places where a F. fusca population is under threat of F. sanguinea. In such situations, abundance of F. fusca within the territory of wood ants is 5-6 times as high as that outside the territory. Thus, to F. fusca, living as a submissive species in a territory of wood ants, the advantages of the protection of its nests from periodic raids of F. sanguinea outweigh the permanent disadvantages of the close proximity of a dominant species.

Publications:

1) Czechowski W. 1999. Lasius fuliginosus (Latr.) on a sandy dune - its living conditions and interference during raids of Formica sanguinea Latr. (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Annales Zoologici, 49: 117-123.

2) Czechowski W. 2000. Interference of territorial ant species in the course of raids of Formica sanguinea Latr. (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Annales Zoologici, 50: 35-38.

3) Czechowski W. 2001. Differentiation of abundance of Formica fusca L. outside and in territories of Formica rufa L. within a range of Formica sanguinea Latr. raids (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Annales Zoologici (in press).

***

Podpisy do ilustracji:

1. Polydomous and polygynous colony of Formica pratensis in the Gorce Mts (S Poland) - a very rare form of social organization in this wood ant species in Central Europe.

2. Theoretical and practical aspects of artificial colonization of wood ants - one of threats of Polish myrmecology at the turn of the 1980s and the 1990s.

Rada Naukowa

Członkowie Rady Naukowej MiIZ PAN kadencji 2023–2026

(zaktualizowane 18.09.2024)

Pracownicy MiIZ PAN:

- prof. dr hab. Wiesław Bogdanowicz

- dr hab. Przemysław Chylarecki, prof. MiIZ

- prof. dr hab. Roman Gula

- dr hab. Maria Holynski, prof. MiIZ

- prof. dr hab. Dariusz Iwan

- prof. dr hab. Marcin Kamiński

- prof. dr hab. Tadeusz Malewski

- dr hab. Tomasz Mazgajski, prof. MiIZ

- dr hab. Maria Sterzyńska, prof. MiIZ

- dr hab. Karol Szawaryn, prof. MiIZ

- prof. dr hab. Jörn Theuerkauf

- dr hab. Robert Rutkowski, prof. MiIZ

- prof. dr hab. Kazimiera Wioletta Tomaszewska

- dr hab. Magdalena Witek, prof. MiIZ

- prof. dr hab. Mieczysław Wolsan

Przedstawiciele II Wydziału PAN:

- prof. dr hab. Andrzej Dziembowski

- prof. dr hab. Romuald Zabielski

Przedstawiciele innych pracowników naukowych MiIZ PAN:

- dr Justyna Kubacka

- dr hab. Marta Maziarz, prof. MiIZ

- dr Katarzyna Rybarczyk-Mydłowska

Przedstawiciel doktorantów MiIZ PAN:

- mgr Aleksandra Gwiazdowska

Pozostali Członkowie Rady:

- prof. dr hab. Zbigniew Bocheński (Instytut Systematyki i Ewolucji Zwierząt PAN)

- prof. dr hab. Jacek Dabert (Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu)

- dr hab. Ewa Durska (emerytowany prac. Muzeum i Instytut Zoologii PAN)

- prof. dr hab. Joanna Gliwicz (emerytowany prac. Muzeum i Instytut Zoologii PAN)

- prof. dr hab. Michał Grabowski (Uniwersytet Łódzki)

- dr hab. Beata Grzywacz, prof. ISEZ (Instytut Systematyki i Ewolucji Zwierząt PAN)

- dr hab. Łukasz Kajtoch, prof. ISEZ (Instytut Systematyki i Ewolucji Zwierząt PAN)

- prof. dr hab. Joanna Mąkol (Uniwersytet Przyrodniczy we Wrocławiu)

- dr hab. Małgorzata Pilot, prof. UG (Uniwersytet Gdański)

- prof. dr hab. Jarosław Stolarski (Instytut Paleobiologii im. R. Kozłowskiego PAN)

- prof. dr hab. Krzysztof Szpila (Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika w Toruniu)

- dr hab. Jacek Szwedo, prof. UG (Uniwersytet Gdański)

- prof. dr hab. Andrzej Zalewski (Instytut Badania Ssaków PAN)

- dr hab. Michał Żmihorski, prof. IBS (Instytut Badania Ssaków PAN)